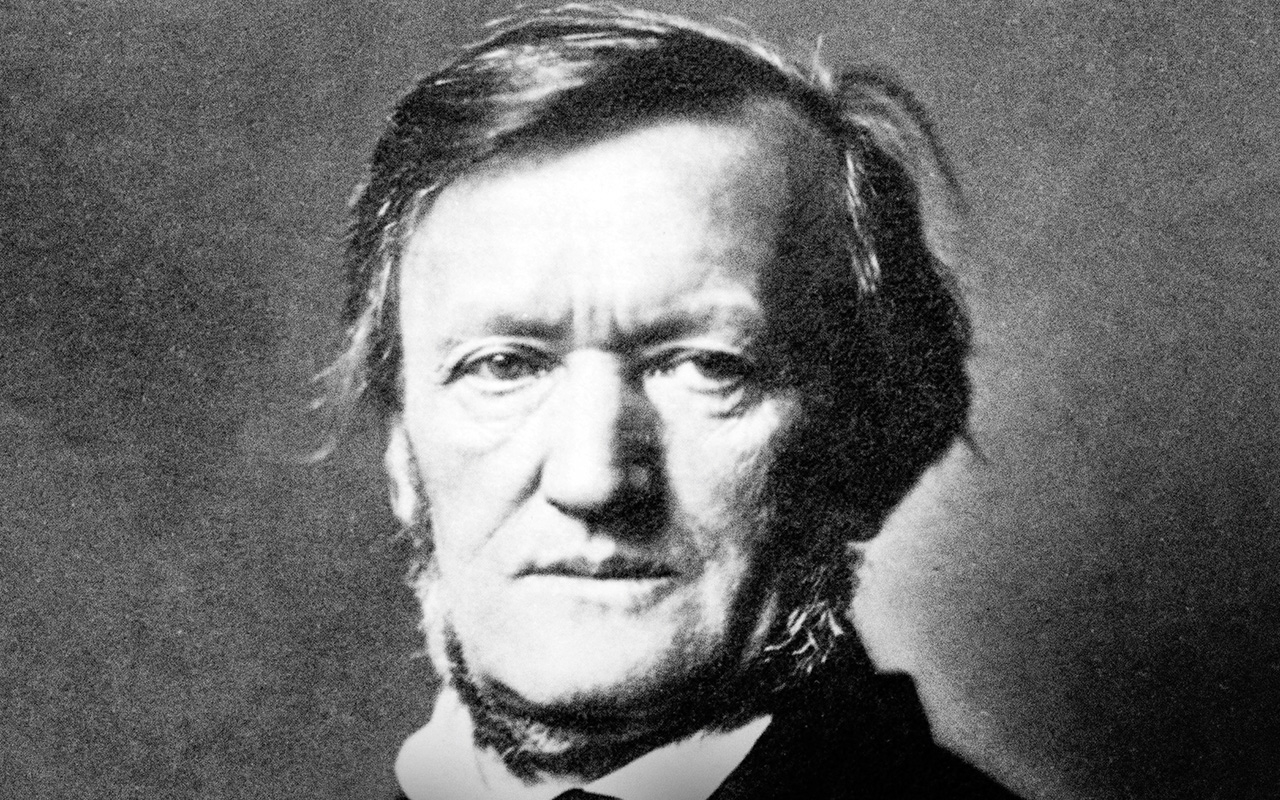

A Biography of Richard Wagner

Introduction

Richard Wagner (1813–1883) stands as one of the most significant and controversial figures in the history of Western classical music. A German composer, theater director, and theorist, Wagner revolutionized opera through his concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art,” which sought to synthesize music, poetry, drama, and visual arts into a unified artistic expression. His innovative use of leitmotifs, complex harmonies, and expansive orchestral textures profoundly influenced subsequent generations of composers and reshaped the landscape of musical theater. Beyond his musical genius, Wagner’s life was marked by political exile, financial struggles, and a complex personal life, all of which contributed to his enduring legacy and the ongoing debates surrounding his character and artistic contributions. This biography will delve into the various facets of Wagner’s life, from his formative years to his monumental compositions and lasting impact on the world of music.

Childhood and Early Life

Wilhelm Richard Wagner was born on May 22, 1813, in Leipzig, Germany, as the ninth child in his family. His father, Carl Friedrich Wagner, was a police actuary, and his mother was Johanna Rosine Wagner. Carl Friedrich died just six months after Richard’s birth, and his mother soon after married Ludwig Geyer, an actor, painter, and poet, who became a significant figure in young Richard’s life. Geyer’s artistic background heavily influenced Wagner’s early years, exposing him to the world of theater and art from a very young age. Several of his elder sisters also pursued careers as opera singers or actresses, further immersing him in a theatrical environment.

Wagner’s formal education was somewhat unconventional. He was a negligent scholar at the Kreuzschule in Dresden and later at the Nicholaischule in Leipzig. Despite his academic shortcomings, he showed an early and intense interest in music and literature. He was largely self-taught in piano and composition, and he avidly read the works of literary giants such as William Shakespeare, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Friedrich Schiller. This early exposure to drama and poetry, combined with his burgeoning musical talent, laid the groundwork for his future artistic endeavors, particularly his ambition to unify these art forms in his operas.

Youth and Early Career

Wagner’s youth was marked by a passionate, if sometimes undisciplined, pursuit of his artistic ambitions. He enrolled at Leipzig University, drawn by the allure of student life, but his academic record remained inconsistent. Nevertheless, he dedicated himself earnestly to composition. Impatient with traditional academic methods, he spent only six months studying with Theodor Weinlig, cantor of the Thomasschule, gaining a foundational understanding of composition. His true education, however, came from an intensive personal study of the scores of master composers, particularly the quartets and symphonies of Ludwig van Beethoven, whose revolutionary spirit deeply resonated with him.

In 1833, his Symphony in C Major was performed at the Leipzig Gewandhaus concerts, an early sign of his burgeoning talent. That same year, he took on a role as an operatic coach in Würzburg, where he composed his first opera, Die Feen (The Fairies), based on a fantastical tale by Carlo Gozzi. Despite his efforts, he failed to secure a production for Die Feen in Leipzig. His personal life also took a significant turn when he fell in love with Wilhelmine (Minna) Planer, an actress with a provincial theatrical troupe in Magdeburg, whom he married in 1836. His second opera, Das Liebesverbot (The Ban on Love), inspired by Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, premiered in Magdeburg but proved to be a complete disaster, further highlighting the challenges he faced in establishing his career.

Driven by a desire for recognition and fleeing from mounting debts, Wagner embarked on a three-year period in Paris starting in 1839. This period proved to be calamitous. Despite a recommendation from the influential German-French composer Giacomo Meyerbeer, Wagner found it impossible to penetrate the exclusive circles of the Opéra. He struggled financially, resorting to musical journalism and hackwork to survive among a community of impoverished German artists. Despite these hardships, he completed Rienzi (based on Bulwer-Lytton’s novel) in 1840 and, in 1841, composed Der fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman), an opera based on the legend of a cursed ship captain. This work marked a significant turning point, as it was his first opera to truly embody his unique artistic vision.

Adult Life and Artistic Development

Return to Dresden and Early Successes

In 1842, at the age of 29, Wagner returned to Dresden, where his opera Rienzi was triumphantly performed on October 20. This success led to his appointment as conductor of the court opera in 1843, a prestigious position he held until 1849. His next opera, The Flying Dutchman, premiered in Dresden on January 2, 1843, but was less immediately successful than Rienzi. Audiences, accustomed to the French-Italian operatic tradition, were initially perplexed by its innovative integration of music and dramatic content. However, Tannhäuser, which premiered on October 19, 1845, and was based on Germanic legends, gradually gained popularity despite initial critical resistance. These works solidified his reputation as a significant composer, though his revolutionary ideas often clashed with the conservative tastes of the establishment.

Political Exile and Artistic Evolution

Wagner’s radical political views led to his involvement in the German revolution of 1848–49. He actively participated in the Dresden uprising of 1849, advocating for social and artistic reforms that would have shifted control of the opera from the court to a national theater managed by artists. When the uprising failed, a warrant was issued for his arrest, forcing him to flee Germany. He was unable to attend the premiere of his opera Lohengrin in Weimar on August 28, 1850, which was conducted by his friend Franz Liszt.

For the next 15 years, Wagner lived in exile, primarily in Zürich, Switzerland. This period, from 1849 to 1858, was highly productive intellectually, though he composed no new operas. Instead, he dedicated himself to writing influential prose works that articulated his theories on art and revolution. These included Die Kunst und die Revolution (Art and Revolution), Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft (The Art Work of the Future), Eine Mitteilung an meine Freunde (A Communication to My Friends), and Oper und Drama (Opera and Drama). In Oper und Drama, he outlined his vision for a new type of musical stage work, which he preferred to call “drama” rather than “music drama.” This concept, later known as Gesamtkunstwerk, aimed to unify all art forms into a single, cohesive artistic expression.

During this time, he also began to develop his monumental tetralogy, Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung), based on the Siegfried legend and Norse myths. The Ring cycle, comprising Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung, became the embodiment of his mature style, characterized by a continuous vocal-symphonic texture woven from basic thematic ideas known as leitmotifs. These leitmotifs, or “leading motives,” were not merely labels but underwent constant development and transformation, reflecting the psychological evolution of the drama. His work on The Ring was temporarily suspended due to the immense scale of the project and the impossibility of staging it at the time. His philosophical outlook also shifted from an optimistic social philosophy to a more pessimistic, world-renouncing view, influenced by his discovery of Arthur Schopenhauer’s philosophy. This period also saw the composition of Tristan und Isolde (1857–59), a work deeply influenced by his hopeless love for Mathilde Wesendonk, which led to the separation from his wife, Minna.

Return to Germany and Bayreuth

In 1861, an amnesty allowed Wagner to return to Germany. After a period of further financial struggles and a disastrous attempt to stage a revised Tannhäuser in Paris, his fortunes dramatically changed in 1864. Louis II, the young king of Bavaria, a fervent admirer of Wagner’s art, came to his rescue. King Louis provided Wagner with financial support and a villa in Munich, enabling him to complete his works. During the next six years, Munich saw successful productions of many of Wagner’s operas, including the premieres of Tristan (1865), Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1869), Das Rheingold (1869), and Die Walküre (1870).

Despite the king’s patronage, Wagner’s controversial personal life and constant financial demands led to opposition in Munich. His affair with Cosima von Bülow, the daughter of Franz Liszt and wife of his conductor Hans von Bülow, resulted in three children and eventually their marriage in 1870. To avoid further scandal, Wagner moved to Triebschen on Lake Lucerne. However, his ultimate goal was to create a dedicated festival theater for the performance of his Ring cycle.

In 1869, Wagner resumed work on The Ring. He envisioned a new type of theater specifically designed for his unique musical dramas. He found a suitable site in Bayreuth, Bavaria, and began touring Germany to raise funds for the project. The foundation stone for the Festspielhaus (Festival Theater) was laid in 1872, and in 1874, Wagner moved into his new home, Wahnfried. Despite immense artistic, administrative, and financial challenges, The Ring received its triumphant first complete performance at the new Festspielhaus in Bayreuth on August 13, 14, 16, and 17, 1876. This marked the realization of his lifelong dream and established Bayreuth as a pilgrimage site for Wagner enthusiasts.

Main Compositions

Richard Wagner’s compositional output, though relatively small in number compared to some of his contemporaries, is monumental in its scope and influence. His works are primarily operas, which he redefined as “music dramas,” emphasizing the seamless integration of music, text, and stagecraft. Here are some of his most significant compositions:

•Der fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman, 1843): This opera marks Wagner’s first significant step towards his mature style. Based on a popular legend, it explores themes of redemption through love and features a continuous musical flow, a departure from the traditional number opera format.

•Tannhäuser (1845): Drawing from German legends, Tannhäuser delves into the conflict between sacred and profane love. It showcases Wagner’s developing use of leitmotifs and his ability to create rich, evocative musical landscapes.

•Lohengrin (1850): A romantic opera based on the legend of the Swan Knight, Lohengrin is celebrated for its lyrical beauty and dramatic power. The famous Bridal Chorus from this opera remains one of the most recognizable pieces of classical music.

•Tristan und Isolde (1865): Considered a landmark in the history of music, Tristan und Isolde is a passionate exploration of love and death. Its revolutionary harmonic language, particularly the “Tristan chord,” pushed the boundaries of tonality and profoundly influenced the development of modern music.

•Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Mastersingers of Nuremberg, 1869): This is Wagner’s only mature comedy, a warm and humanistic portrayal of artistic tradition and innovation. It stands in contrast to his more mythical works, showcasing his versatility as a composer.

•Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung, 1869–76): This monumental cycle of four music dramas—Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung—is Wagner’s magnum opus. Spanning over 15 hours of music, The Ring explores themes of power, greed, love, and redemption, all unified by an intricate web of leitmotifs. It is an unparalleled achievement in operatic history.

•Parsifal (1882): Wagner’s final opera, Parsifal, is a sacred festival drama based on the legend of the Holy Grail. It is a work of profound spiritual depth and musical complexity, intended for performance only at the Bayreuth Festspielhaus.

Death

Richard Wagner spent the remaining years of his life primarily at Wahnfried in Bayreuth, though he continued to travel, including visits to London and Italy. During this period, he completed his final work, the sacred festival drama Parsifal, which premiered at Bayreuth in 1882. He also dictated his extensive autobiography, Mein Leben (My Life), to his wife Cosima, a project he had begun in 1865.

On February 13, 1883, Richard Wagner died of heart failure in Venice, Italy, at the age of 69. His body was returned to Bayreuth and buried in the grounds of Wahnfried, in a tomb he had personally prepared. His death marked the end of an era in music, but his legacy continued to grow, with the Bayreuth Festspielhaus staging yearly festivals of his works, interrupted only by the two World Wars.

Conclusion

Richard Wagner’s impact on music and culture is immeasurable. His revolutionary approach to opera, characterized by the Gesamtkunstwerk and the innovative use of leitmotifs, transformed the genre and laid the groundwork for much of 20th-century music. His influence extended beyond the musical realm, touching upon literature, philosophy, and theater, and sparking debates that continue to this day.

Comments are closed