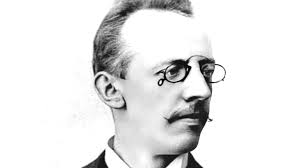

Vítězslav Novák – A Complete Biography

Introduction

Vítězslav Novák (1870–1949) was a central figure of early-20th-century Czech music: a pupil of Antonín Dvořák, a leading proponent of musical nationalism, and a formidable teacher whose students helped shape Czech and Slovak musical life between the wars. His language fused late-Romantic breadth with Impressionist color and the modal contours of Moravian and Slovak folk song.

Childhood

Born Viktor Novák on December 5, 1870, in Kamenice nad Lipou, Southern Bohemia, he was the elder son of a local physician. After his father died when he was eleven, the family moved to Jindřichův Hradec, where the boy’s musical gifts—initially fostered by violin and piano lessons—were further encouraged by local teachers. In his teens he began composing and, like many of his generation, adopted the proudly Czech given name “Vítězslav.”

Youth

In 1889 Novák went to Prague on a scholarship nominally to study law at Charles University, but his real passion was music. He enrolled at the Prague Conservatory, studying piano with Josef Jiránek, harmony with Karel Knittl, counterpoint with Karel Stecker, and—after 1891—composition in Dvořák’s master class. By the late 1890s he was traveling in Moravia and Slovakia, collecting and studying folk melody and rhythm—work that decisively marked his style.

Adulthood

Novák emerged around 1900 with a distinct voice that blended folk modality with the sheen of French Impressionism and the orchestral sweep of Strauss. In 1909 he joined the Prague Conservatory faculty, becoming one of the most influential composition teachers in the region; among the notable pupils shaped directly or indirectly by him were Alois Hába, Alexander Moyzes, Eugen Suchoň, and Ján Cikker. He was deeply involved in Prague’s cultural debates—often fierce—about the direction of modern Czech music, and he later took on administrative roles in the newly independent Czechoslovakia’s musical institutions.

Through the 1930s and World War II, Novák’s large-scale choral-symphonic works carried a strongly patriotic tone. In retirement he wrote a candid memoir, O sobě a jiných (Of Myself and Others, published posthumously in 1970), reflecting on colleagues and the artistic battles of his era.

Major Compositions

Novák wrote across every major genre. Highlights include:

- In the Tatras (V Tatrách), Op. 26 (1902): a tone poem whose sweeping arcs evoke the High Tatras and mark his first widely recognized orchestral success.

- Eternal Longing (O věčné touze), Op. 33 (1903–05): a lush symphonic poem showing Impressionist influence.

- Wallachian Dances (Valašské tance), Op. 34 (1904) and Slovak Suite (Slovácká svita), Op. 32 (1903): stylized folk idioms integrated into concert music.

- Toman and the Wood Nymph (Toman a lesní panna), Op. 40 (1906–07), Lady Godiva Overture, Op. 41 (1907), and Pan, Op. 43 (1910): orchestral scores marrying narrative impulse with brilliant color.

- Storm (Bouře), Op. 42 (1908–10): a large cantata cementing his reputation in vocal-orchestral writing.

- Operas: Zvíkovský rarášek (The Imp of Zvíkov), Op. 49 (1913–14); Karlštejn, Op. 50 (1914–15); Lucerna (The Lantern), Op. 56 (1919–22); and Dědův odkaz (Grandfather’s Legacy), Op. 57 (1922–25).

- Autumn Symphony (Podzimní symfonie), Op. 62 (1931–34): a vast choral-symphonic fresco from his interwar “renewal.”

- South Bohemian Suite (Jihočeská suita), Op. 64 (1936–37): pastoral panels from his native region.

- Wartime scores with patriotic resonance: De Profundis, Op. 67 (1941), Saint Wenceslas Triptych (Svatováclavský triptych), Op. 70 (1942), and the May Symphony (Májová symfonie), Op. 73 (1943; premiered 1945).

His catalog also includes notable piano works (such as the Sonata Eroica, Op. 24), chamber music, choral cycles, and songs.

Death

Novák died on July 18, 1949, in Skuteč, Eastern Bohemia. By then he was recognized as a patriarch of Czech musical life: a composer rooted in national idioms and a teacher whose studio radiated influence across Central Europe.

Conclusion

Vítězslav Novák bridged eras and aesthetics. He absorbed Dvořák’s legacy, transformed folk sources into concert art, and experimented—selectively—with Impressionist harmony, all while mentoring a generation that carried his nationalist ethos into new stylistic territories. Today his orchestral tone poems (not least In the Tatras), his choral-symphonic frescoes, and his operas are being re-examined and recorded anew, underscoring his place at the heart of Czech modernism.

Comments are closed