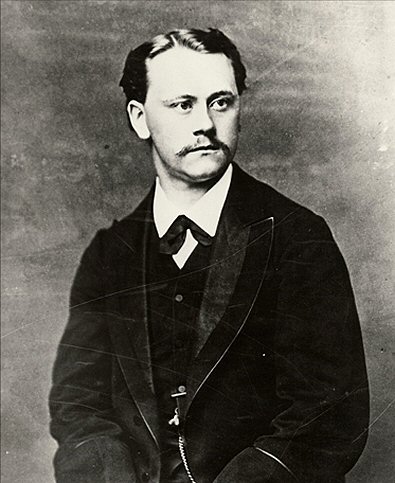

Henri Duparc – A Complete Biography

Introduction

Henri Duparc (1848–1933) was a French late-Romantic composer whose reputation rests on a remarkably small but exquisite catalogue—especially 17 mélodies that helped expand French art song into something symphonic in sweep and psychological depth. Intensely self-critical and plagued by ill health, he stopped composing in his thirties, yet his songs—“L’invitation au voyage,” “Phidylé,” “La vie antérieure,” “Chanson triste,” among others—remain touchstones for singers and pianists.

Childhood

Born in Paris on January 21, 1848, Marie Eugène Henri Fouques Duparc grew up in an educated, comfortable family. He attended the Jesuit College of Vaugirard, where his piano teacher was César Franck—a relationship that proved decisive, steering him from keyboard virtuosity toward composition.

Youth

In his late teens and early twenties, Duparc studied privately with Franck and began composing piano pieces and chamber music while absorbing the musical cross-currents of the day. A formative journey in 1869 to hear Wagner (with the young Vincent d’Indy) left a lasting stylistic imprint. After serving in the Franco-Prussian War, he married Ellie (Ellen) Mac Swiney in November 1871. That same year he joined Saint-Saëns and Romain Bussine as a founding member of the Société nationale de musique, the influential association dedicated to promoting new French music.

Adulthood

The 1870s and early 1880s were Duparc’s most productive years. Alongside his songs, he ventured into orchestral writing with the symphonic poem Aux étoiles (1874; later revised) and Lénore (1874–75), and he even planned an opera, Roussalka, eventually destroyed in his fierce self-editing. The songs themselves broadened the scale and drama of the French mélodie, fusing poetic prosody with a more “symphonic” conception of form.

In 1885, at just 37, Duparc abruptly ceased composing due to a debilitating condition then diagnosed as neurasthenia. He turned to drawing and painting, later suffering progressive vision loss that led to total blindness. He spent much of his later life in Switzerland (La Tour-de-Peilz, near Vevey) before dying in 1933. Contemporaries and later writers often cited his heightened sensitivity and perfectionism as causes for both the small output and its unusual refinement.

Major Compositions

Though slender, Duparc’s output is extraordinarily concentrated. His mélodies—frequently performed in both piano and orchestral versions—include:

- “L’invitation au voyage” and “La vie antérieure” (texts by Charles Baudelaire), emblematic of his sensuous harmonic language.

- “Phidylé,” a radiant setting of Leconte de Lisle, initially for high voice and piano and later orchestrated; it rises from languor to rapture in a single arch.

- “Extase,” on a poem by Jean Lahor (Henri Cazalis), one of his finest examples of voice and piano breathing as one.

- “Au pays où se fait la guerre” (Théophile Gautier), “Le manoir de Rosemonde” (Robert de Bonnières), and “La vague et la cloche” (François Coppée), each showcasing his knack for drama within the song form.

- “Chanson triste,” “Soupir,” “Sérénade,” and “Romance de Mignon,” early yet enduring pillars of his songbook.

Among the orchestral works, Aux étoiles (originally part of a projected Poème nocturne) and the symphonic poem Lénore stand out; performances and source materials survive, attesting to their atmospheric, Wagner-tinged palette.

Duparc also returned sporadically to music in later years: “Testament” (1883; orchestrated 1900–01) is a prayerful outlier that hints at the spiritual focus of his final decades.

Death

Duparc died on February 12, 1933, in Mont-de-Marsan, France, and is buried at Père-Lachaise in Paris.

Conclusion

Henri Duparc occupies a singular place in music history: a composer who wrote little, destroyed much, and yet shaped the French mélodie so decisively that his songs have never left the repertory. His art distills Wagnerian chromaticism, Franckian discipline, and Parnassian poetry into scenes of intense inwardness. That he stopped composing so early only deepens the aura: each surviving piece feels necessary, chiselled to its essence, and larger than its modest forces suggest. For these reasons—and for the sheer, enduring beauty of the songs—Duparc remains one of the indispensable voices of nineteenth-century French song.

Comments are closed