Charles-Marie Widor – A Complete Biography

Introduction

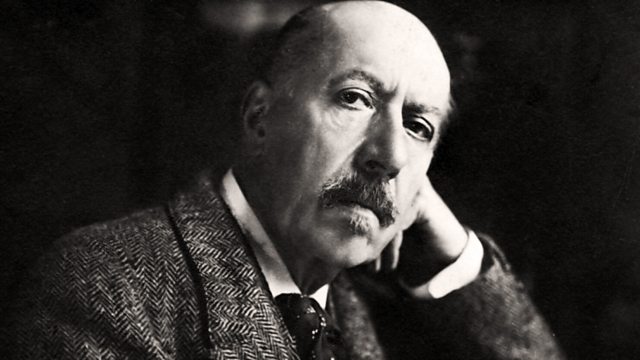

Charles-Marie Widor (1844–1937) stands as one of the defining figures of the French organ tradition in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Organist, composer, pedagogue, editor, and institution builder, he helped shape the sound-world of the “symphonic organ” and the professional standards of modern organ playing. Today, his name is most widely recognized through the brilliant Toccata from his Fifth Organ Symphony, yet his broader legacy rests on a lifetime of service at Paris’s Saint-Sulpice, his influential teaching at the Paris Conservatoire, and a large catalog that extends well beyond the organ loft.

Childhood

Widor was born in Lyon on February 21, 1844, into a family closely tied to the craft and culture of the organ. The environment of workshops, churches, and practical musicianship shaped his earliest learning: he absorbed the instrument not merely as a performer, but as someone who understood how an organ “thinks” mechanically and acoustically. This background mattered later, when he became associated with the great French organ-building renaissance and wrote music that exploited the coloristic resources of large instruments.

Accounts of his early years emphasize both precocity and discipline. As a boy, he was immersed in the liturgical and civic musical life of Lyon, receiving foundational instruction at home before advanced study became possible. By early adolescence, he was already entrusted with serious responsibilities as a church musician—an early sign of the professional stature he would later attain.

Youth

Widor’s formal development accelerated through study in Brussels, where he trained with leading teachers of organ performance and composition. This period broadened his horizons beyond provincial France and placed him in contact with rigorous technique, contrapuntal practice, and the emerging ideals of “serious” organ literature that treated the instrument as capable of symphonic thinking rather than purely functional church service.

By the 1860s he was increasingly connected to the musical currents that ran through Paris. The city offered both opportunity and competition, and Widor’s abilities—particularly as an organist—positioned him well to enter the highest professional circles. His youth, in short, was a transition from local promise to international-level formation.

Adulthood

Widor’s adult career is inseparable from Saint-Sulpice in Paris, where he served as organist for more than six decades, beginning in 1870 and retiring at the end of 1933. The Saint-Sulpice instrument—an iconic example of French nineteenth-century organ building—was not merely his workplace; it was a creative engine. The organ’s scale and expressive range aligned perfectly with Widor’s imagination and contributed to his development of the organ symphony as a mature genre.

Alongside his performance career, Widor became a central figure in French musical education. He succeeded César Franck in a major teaching role at the Paris Conservatoire and later held prominent positions there, shaping generations of performers and composers. His influence extended through pupils who would define the next era of French organ performance and composition, and through a pedagogy that emphasized technique, stylistic literacy, and a commanding knowledge of core repertoire—especially Bach.

Widor also expanded his institutional footprint after World War I. He played a leading role in establishing the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau in 1921 and served as its first director, strengthening Franco-American musical ties and creating a high-prestige summer training environment that attracted serious young musicians.

Major Compositions

Although Widor wrote in many genres, his reputation rests most securely on his organ works—especially the ten organ symphonies. In these pieces he applied orchestral logic to the organ: clear multi-movement architecture, thematic development, and a palette of color that presumes an instrument capable of wide dynamic and timbral contrast.

The Organ Symphonies (the core legacy)

- Organ Symphony No. 5 (often dated to the late 1870s) contains the celebrated Toccata, a movement whose rhythmic drive and brilliant figurations turned it into a global staple for weddings and festive ceremonies.

- The later symphonies reflect a more concentrated language and a deeper engagement with chant and sacred atmosphere. Two landmarks are:

- Symphonie gothique (Op. 70), composed in the mid-1890s, often associated with a more “cathedral-like” intensity and spiritual gravity.

- Symphonie romane (Op. 73), completed in 1899, which draws on plainchant material and represents a refined culmination of his mature style.

Beyond the organ loft

Widor did not confine himself to organ composition. His catalog includes orchestral works (including symphonies), concertos, chamber music, vocal and choral pieces, and stage works. While these compositions are less frequently programmed today than the organ symphonies, they were part of a career spent in the mainstream of French musical life—not merely within church music.

Editor, author, and musical advocate

A significant dimension of Widor’s legacy is scholarly and pedagogical. He collaborated in the broader revival and professionalization of Bach’s organ repertoire through editorial work undertaken with Albert Schweitzer, contributing to a long-term project that influenced how organists studied and performed Bach in the twentieth century. He also wrote on orchestration and musical craft, reinforcing his image as a musician of wide culture rather than a specialist limited to one instrument.

Death

Widor retired from Saint-Sulpice on December 31, 1933. In his final years he faced declining health, including a serious stroke that affected his body while leaving his intellect largely intact. He died in Paris on March 12, 1937, and was interred at Saint-Sulpice—an ending that symbolically returned him to the church that had framed the most important chapter of his professional life.

Conclusion

Charles Widor’s biography is the story of an artist who modernized a tradition without severing it from its roots. He inherited the French organ world’s craftsmanship and liturgical function, then transformed it through symphonic ambition, institutional leadership, and uncompromising pedagogy. The Fifth Symphony’s Toccata may be his most visible monument, but the deeper achievement is broader: he helped define what the modern organist could be—virtuoso, architect of large forms, interpreter of Bach, and cultural leader. His music continues to be performed not only because it is effective and brilliant, but because it embodies a particular French ideal of grandeur, clarity, and disciplined imagination.

Comments are closed