The Enigmatic Virtuoso: A Biography of Niccolò Paganini

Introduction

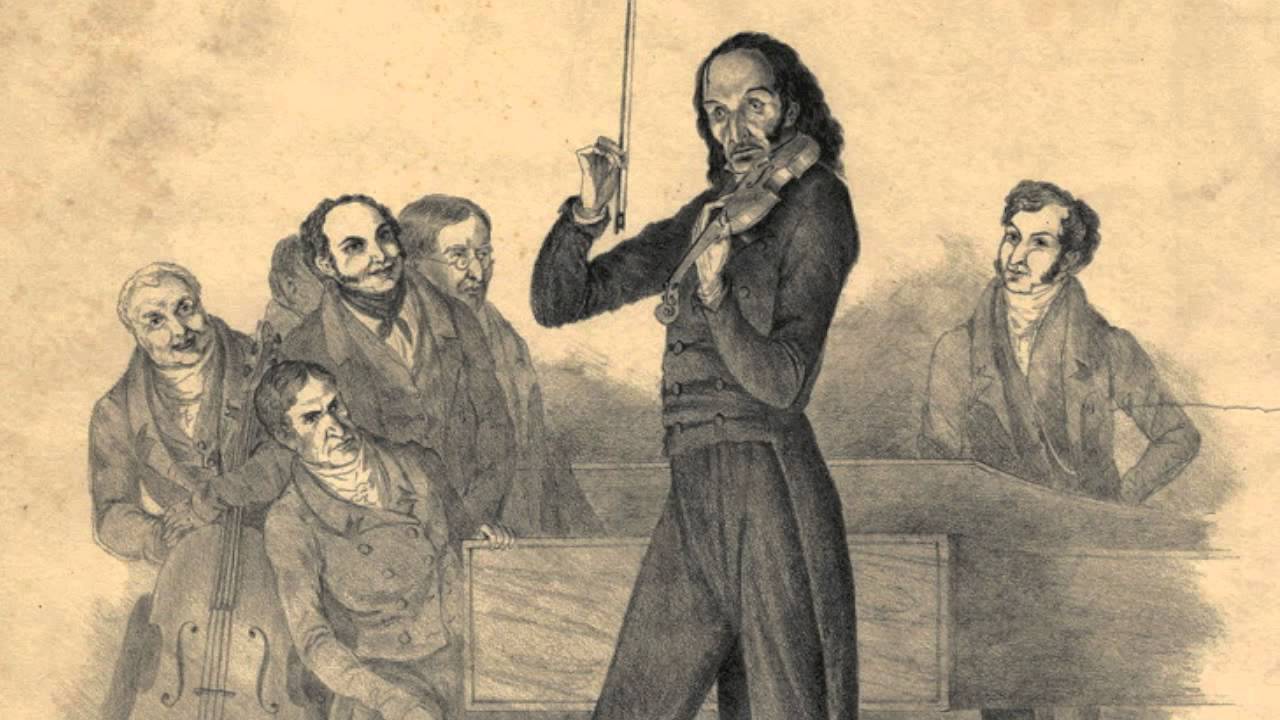

Niccolò Paganini (1782–1840) stands as one of the most iconic and enigmatic figures in the history of classical music. An Italian violinist and composer, he captivated audiences across Europe with his unparalleled virtuosity, revolutionary techniques, and a stage presence that bordered on the supernatural. Often dubbed “the Devil’s Violinist” due to his astounding abilities and the rumors that circulated about his pacts with infernal forces, Paganini redefined what was possible on the violin and left an indelible mark on musical performance and composition. His influence extended far beyond his lifetime, inspiring generations of musicians and composers, including such luminaries as Franz Liszt, Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, and Sergey Rachmaninoff, who drew inspiration from his groundbreaking works, most notably his 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, Op. 1.

Born into humble beginnings in Genoa, Paganini displayed prodigious musical talent from a very young age. His early studies under various local teachers and later with renowned pedagogues like Alessandro Rolla and Ferdinando Paer quickly revealed a genius that surpassed conventional instruction. Throughout his life, Paganini’s career was a whirlwind of triumphant concerts, personal struggles, and a relentless pursuit of musical innovation. This biography will delve into the life of this extraordinary artist, exploring his childhood, youth, and adulthood, examining his major compositions, recounting the circumstances of his death, and ultimately assessing his enduring legacy in the world of music.

Childhood

Niccolò Paganini was born in Genoa, then the capital of the Republic of Genoa, on October 27, 1782. He was the third of six children born to Antonio Paganini and Teresa Bocciardo. Antonio Paganini, though an unsuccessful ship chandler, supplemented his income by playing the mandolin and teaching it to his son. At the tender age of five, Niccolò began his musical journey with the mandolin under his father’s tutelage, transitioning to the violin by the age of seven.

His innate musical talents were quickly recognized, leading to numerous scholarships for violin lessons. The young Paganini initially studied with local violinists such as Giovanni Servetto and Giacomo Costa. However, his rapid progress soon outstripped their capabilities. Recognizing his son’s extraordinary potential, Antonio Paganini took Niccolò to Parma to seek guidance from the celebrated violinist Alessandro Rolla. Upon hearing Paganini play, Rolla was so impressed that he immediately referred him to his own teacher, Ferdinando Paer, and subsequently to Paer’s teacher, Gasparo Ghiretti. This early, intensive training laid the foundation for the unparalleled technical mastery that would define Paganini’s career.

Youth

The political landscape of Italy underwent significant upheaval in March 1796 with the French invasion of northern Italy, which destabilized Genoa. The Paganini family sought refuge in their country property in Romairone, near Bolzaneto. It was during this period of displacement that Paganini is believed to have further developed his relationship with the guitar. Although he mastered the instrument, he preferred to play it in private, intimate settings rather than in public concerts, later referring to it as his “constant companion” during his concert tours.

By 1800, Paganini and his father relocated to Livorno, where Niccolò performed in concerts while his father resumed his maritime work. In 1801, at the age of 18, Paganini was appointed first violin of the Republic of Lucca. Despite this official position, a significant portion of his income came from freelance performances. During this time, his burgeoning fame as a violinist was unfortunately matched by his growing reputation as a gambler and philanderer.

In 1805, Lucca was annexed by Napoleonic France and ceded to Napoleon’s sister, Elisa Bonaparte. Paganini entered the service of the Baciocchi court as a violinist, also providing private lessons to Elisa’s husband, Felice, for a decade. Historical accounts suggest that Paganini and Elisa Bonaparte Baciocchi were also engaged in a romantic affair during this period. When Baciocchi became the Grand Duchess of Tuscany in 1807 and her court moved to Florence, Paganini was part of her entourage. However, by late 1809, he left the court to resume his career as a freelance musician, a decision that marked the beginning of his ascent to continental fame.

Adulthood

Following his departure from the Baciocchi court, Paganini embarked on a period of extensive touring throughout Europe, solidifying his reputation as a traveling virtuoso. Initially, his fame was largely confined to the regions around Parma and Genoa, but a pivotal concert at La Scala in Milan in 1813 marked a turning point, bringing him widespread recognition. This success attracted the attention of other prominent musicians, though it also sparked intense rivalries with contemporaries such as Charles Philippe Lafont and Louis Spohr.

Paganini’s technical prowess and showmanship were legendary. He was celebrated for his ability to perform incredibly complex passages, often incorporating harmonics, pizzicato effects, and innovative fingering techniques. His performances were not merely displays of technical skill but also theatrical events, with Paganini sometimes severing violin strings during a piece and continuing to play on the remaining ones, further fueling the mystique surrounding him. Audiences were said to have been moved to tears by his tender passages and astonished by his ferocity.

His fame reached its zenith with a grand European concert tour that commenced in Vienna in August 1828. Over the next few years, he captivated audiences in major cities across Germany, Poland, Bohemia, Paris, and Britain. In 1827, Pope Leo XII honored him with the prestigious Order of the Golden Spur, a testament to his immense cultural impact.

Throughout his life, Paganini was plagued by chronic illnesses. While definitive medical proof is lacking, it has been theorized that he may have suffered from Marfan syndrome or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, conditions that could explain his unusually long limbs and extraordinary flexibility, which undoubtedly contributed to his unique violin technique. His demanding concert schedule and extravagant lifestyle likely exacerbated his health issues. He was diagnosed with syphilis as early as 1822, and the mercury and opium treatments he received had severe physical and psychological side effects. In 1834, while in Paris, he was also treated for tuberculosis.

By September 1834, Paganini decided to end his concert career and returned to Genoa. Contrary to popular belief that he wished to keep his musical secrets, he dedicated his time to publishing his compositions and violin methods. He also took on a few students, though none found him particularly helpful or inspirational. In 1835, he briefly served Archduchess Marie Louise of Austria, Napoleon’s second wife, in Parma, tasked with reorganizing her court orchestra. However, conflicts with the musicians and the court prevented his vision from being fully realized.

Major Compositions

Paganini’s compositional output, though not as extensive as some of his contemporaries, is remarkable for its innovative demands on violin technique and its lasting influence on subsequent generations of composers. His works are characterized by their dazzling virtuosity, intricate melodic lines, and a pioneering use of extended techniques that pushed the boundaries of what was thought possible on the violin.

Undoubtedly, his most famous and influential works are the 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, Op. 1. Composed between 1801 and 1807, these pieces are a cornerstone of the violin repertoire, showcasing a wide array of technical challenges including rapid arpeggios, double stops, left-hand pizzicato, and harmonics. They were initially intended as studies for his own practice but quickly became a benchmark for violinists worldwide. The Caprices have inspired numerous composers to write their own variations or to incorporate Paganini’s themes into their works, notably Franz Liszt (Grandes études de Paganini), Robert Schumann (Studies after Caprices by Paganini), Johannes Brahms (Variations on a Theme by Paganini), and Sergey Rachmaninoff (Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini).

Among his other significant works are his violin concertos, particularly the Violin Concerto No. 1 in D major, Op. 6, and the Violin Concerto No. 2 in B minor, Op. 7, famously known as “La Campanella” (The Little Bell) due to its bell-like effects. He also composed the Violin Concerto No. 4 in D minor. These concertos are characterized by their lyrical melodies, dramatic flair, and, of course, their demanding solo parts that highlight Paganini’s extraordinary technical abilities.

Beyond his works for solo violin and violin with orchestra, Paganini also explored chamber music. He composed 12 Sonatas for Violin and Guitar and 6 Quartets for Violin, Viola, Cello, and Guitar. These compositions demonstrate his affection for the guitar, an instrument he considered his “constant companion”. While less frequently performed than his violin works, they offer a glimpse into his more intimate compositional style and his versatility as a musician.

Paganini’s innovations in violin technique, including his extensive use of harmonics, pizzicato, and new fingering methods, revolutionized violin playing. His flamboyant showmanship, such as playing on a single string after intentionally breaking others, further cemented his legendary status and influenced later virtuosi like Pablo Sarasate and Eugène Ysaÿe. His legacy as a composer lies not only in the brilliance of his individual pieces but also in how he expanded the expressive and technical possibilities of the violin, forever changing the landscape of classical music.

Death

Paganini’s final years were marked by declining health and financial woes. In 1836, he returned to Paris with an ill-fated venture to establish a casino. The immediate failure of this enterprise left him in significant financial ruin, forcing him to auction off his personal effects, including his cherished musical instruments, to recoup his losses.

By Christmas of 1838, his health had severely deteriorated, prompting him to leave Paris for Marseille, and shortly thereafter, he traveled to Nice. His condition continued to worsen in Nice. In May 1840, recognizing his imminent death, the Bishop of Nice dispatched a local parish priest to administer the last rites. However, Paganini, perhaps believing the sacrament to be premature, refused it.

A week later, on May 27, 1840, Niccolò Paganini died at the age of 57 from internal hemorrhaging. The circumstances surrounding his death, coupled with his refusal of the last rites and the persistent rumors of his association with the devil—a legend he himself had, at times, encouraged through his theatrical performances—led the Church to deny him a Catholic burial in his hometown of Genoa.

The controversy over his burial dragged on for years. It took four years and a direct appeal to the Pope before his body was permitted to be transported to Genoa, though it remained unburied. His remains were finally interred in 1876, 36 years after his death, in a cemetery in Parma. This prolonged dispute over his final resting place further cemented the mystique and controversy that surrounded Paganini throughout his life and even beyond.

Conclusion

Niccolò Paganini remains an unparalleled figure in the annals of classical music, a virtuoso whose technical brilliance and magnetic stage presence revolutionized violin playing and left an enduring legacy. From his humble beginnings in Genoa to his meteoric rise as a European sensation, Paganini consistently pushed the boundaries of musical performance, inspiring awe and, at times, fear among his audiences. His ability to conjure sounds previously unheard from the violin, coupled with his dramatic flair, earned him the moniker “the Devil’s Violinist,” a legend that he shrewdly cultivated and that continues to fascinate to this day.

His compositions, particularly the 24 Caprices, stand as monumental achievements in the violin repertoire, challenging performers with their extreme technical demands while simultaneously offering profound musicality. These works, along with his concertos and chamber pieces, continue to be studied and performed globally, a testament to their timeless appeal and the genius of their creator. Paganini’s influence extended beyond his own instrument, inspiring a new generation of composers to explore the limits of virtuosity in their own works, fundamentally shaping the Romantic era of music.

Despite the personal struggles, chronic illnesses, and financial misfortunes that marked his later years, Paganini’s dedication to his art never wavered. His life was a testament to the power of talent, relentless practice, and an unwavering commitment to innovation. As he famously quipped, “I am not handsome, but when women hear me play, they come crawling to my feet”. This blend of self-awareness, confidence, and a touch of theatricality perfectly encapsulates the man who was Niccolò Paganini—a true musical titan whose legend continues to resonate, cementing his place as perhaps the greatest violinist who ever lived.

Comments are closed