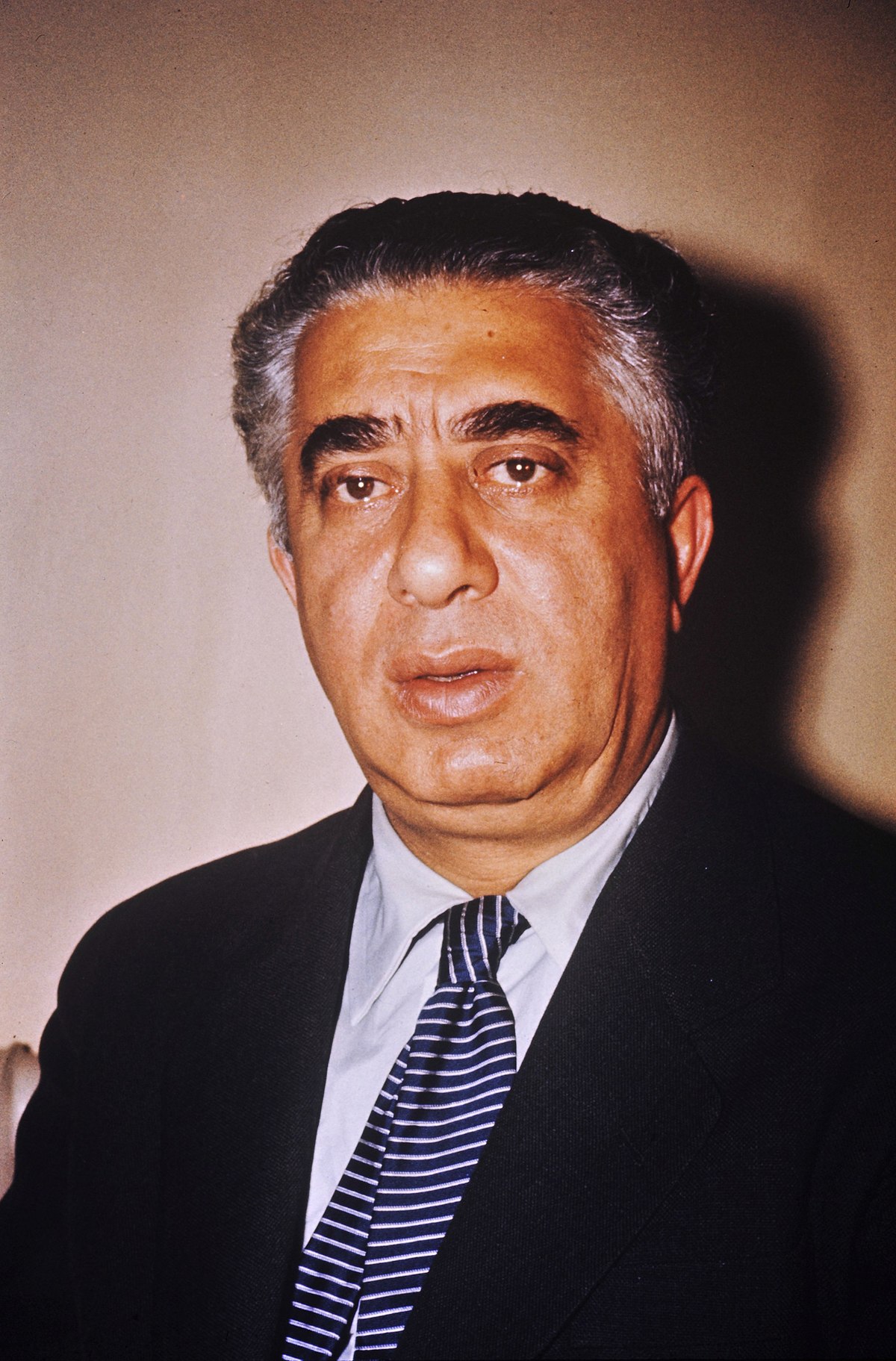

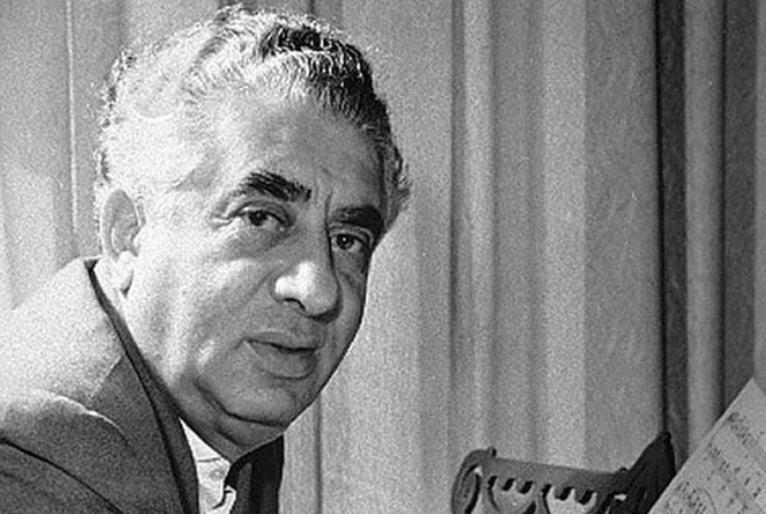

Aram Khachaturian: A Complete Biography

Introduction

Aram Khachaturian was one of the most distinctive and celebrated composers of the Soviet era, renowned for his masterful fusion of classical form with the vivid musical idioms of Armenian folk tradition. He earned international acclaim through his ballets, symphonies, and concertos, and he remains a towering figure in the history of twentieth-century music. With works like the ballet Spartacus and the famous Sabre Dance from Gayane, Khachaturian introduced the world to a vibrant and emotionally potent musical language. His music not only defined Soviet musical culture but also showcased the rich heritage of the Caucasus region.

Childhood

Aram Ilyich Khachaturian was born on June 6, 1903, in Tiflis (now Tbilisi), the capital of present-day Georgia, which was then part of the Russian Empire. He was born into a humble Armenian family—his father was a bookbinder, and the family spoke Armenian at home while being immersed in a multicultural environment. Despite lacking formal musical training in his early years, Khachaturian demonstrated a natural affinity for music. He was deeply influenced by the traditional music of Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan, which he heard during community festivals and family gatherings. These early experiences planted the seeds for his lifelong passion for folk music.

Khachaturian’s early education was in science, as his family did not envision a future for him in music. In 1921, he moved to Moscow to join his brother, Suren, who was a stage director. There, Khachaturian enrolled in biology studies at the Moscow State University but soon pivoted toward music, setting the stage for an extraordinary transformation from self-taught amateur to globally respected composer.

Youth

In 1922, Khachaturian began formal music studies at the Gnessin Musical Institute, where he took cello lessons and studied music theory. His extraordinary talent quickly emerged, and by 1929, he entered the Moscow Conservatory under the guidance of prominent Russian composer Nikolai Myaskovsky, who became a major influence on his development.

During his student years, Khachaturian composed prolifically. His works began to reflect a unique voice—a dynamic synthesis of classical structures and Eastern folk rhythms and melodies. One of his early major successes was the Piano Concerto in D-flat major (1936), which established him as a composer of serious merit in the Soviet Union.

The success of this concerto led to wide recognition, and Khachaturian began receiving commissions for film scores, stage music, and orchestral works. He became a prominent figure within the Union of Soviet Composers and was championed by the Soviet government as a representative of the USSR’s cultural achievements.

Adulthood

Khachaturian’s adult years were marked by both artistic triumph and political controversy. He composed some of his most iconic works during this time, including the Violin Concerto (1940), dedicated to the great violinist David Oistrakh, and the ballet Gayane (1942), which featured the world-famous Sabre Dance. These works won him prestigious awards, including the Stalin Prize and the title of People’s Artist of the USSR.

Despite official support, Khachaturian’s relationship with the Soviet authorities was not always smooth. In 1948, along with fellow composers Dmitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokofiev, he was denounced during the Zhdanov Purge for “formalism”—a charge meaning his music was too Western and insufficiently aligned with Soviet ideals. Deeply affected, Khachaturian publicly apologized and worked to realign his artistic output with the principles of socialist realism. By 1950, he had regained favor and was even appointed as a professor at both the Moscow Conservatory and the Gnessin Institute.

Khachaturian also became an ambassador of Soviet culture abroad, traveling extensively and representing the USSR at international music conferences and festivals. His reputation as a gifted teacher grew, and he mentored many younger composers, contributing significantly to the future of Soviet music.

Major Compositions

Khachaturian’s compositional output spans many genres, but he is best known for his concertos and ballets. His most enduring works include:

- Piano Concerto in D-flat major (1936): A bold, rhythmic, and harmonically adventurous work that first brought him widespread acclaim.

- Violin Concerto in D minor (1940): Characterized by virtuosic passages and lyrical themes, it is still frequently performed today.

- Cello Concerto in E minor (1946): Less well-known than his other concertos but deeply expressive and technically demanding.

- Gayane (1942): A ballet centered on life in an Armenian collective farm. The Sabre Dance became an international sensation.

- Spartacus (1954): His most ambitious ballet, this work tells the story of the ancient Roman slave uprising. It earned Khachaturian the Lenin Prize in 1959 and remains a staple in ballet companies around the world.

In addition to these, Khachaturian composed symphonies, chamber music, choral works, and numerous film scores. His music is noted for its rhythmic vitality, colorful orchestration, and incorporation of folk elements.

Death

Aram Khachaturian died on May 1, 1978, in Moscow, at the age of 74. He was buried with honors at the Komitas Pantheon in Yerevan, Armenia, alongside other prominent Armenian cultural figures. His legacy was commemorated with the establishment of the Aram Khachaturian Museum in Yerevan in 1982, and a biannual international music competition in his name continues to foster young talent in his homeland and beyond.

Conclusion

Aram Khachaturian’s life and music stand as a testament to the enduring power of cultural identity and artistic innovation. Through his bold fusion of Armenian folk tradition and Western classical forms, he forged a musical language that spoke both to his people and to the world. Despite the political challenges of life in the Soviet Union, he remained committed to his vision and to the expressive potential of music. Today, Khachaturian is celebrated not only as one of the great composers of the twentieth century but also as a symbol of Armenian cultural pride.

Comments are closed