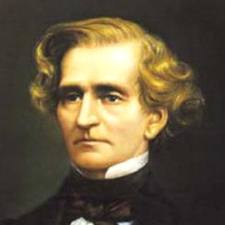

The History of Grande Messe des Morts by Hector Berlioz

Hector Berlioz’s Grande Messe des Morts, Op. 5, also known as his Requiem, stands as one of the most monumental sacred choral works in the Western classical tradition. Composed in 1837, this large-scale setting of the Roman Catholic Requiem Mass not only reflects Berlioz’s visionary orchestral imagination but also marks a key moment in French musical and political history.

Commission and Historical Context

The Grande Messe des Morts was commissioned by the French government to commemorate the soldiers who died during the July Revolution of 1830, which brought King Louis-Philippe to power. The work was intended for a state funeral honoring General Charles-Marie Denys de Damrémont and the French soldiers killed in the Algerian campaign. The ceremony was scheduled to take place at Les Invalides in Paris, a site of national importance where many military heroes were buried.

Berlioz, already known for his daring symphonic writing in works like Symphonie fantastique, was an ideal choice for such an ambitious national project. He accepted the commission with enthusiasm, sensing the opportunity to create something grand and solemn. The Requiem was completed in a matter of months, and it was first performed on December 5, 1837, at Les Invalides, under the direction of François Habeneck.

Structure and Musical Forces

Berlioz’s Grande Messe des Morts is structured in ten movements and scored for an immense ensemble: a large orchestra, four brass bands placed at the corners of the stage or hall, a massive chorus, and tenor soloist. The scale of the work is staggering even by today’s standards:

- Over 400 performers can be involved, including ten pairs of timpani, 16 extra brass players in the offstage bands, and a chorus that can number in the hundreds.

- The most striking use of this grand scale occurs in the “Dies irae” and “Tuba mirum”, where Berlioz unleashes a cataclysmic sonic experience to evoke the terror and majesty of Judgment Day.

Despite this vast orchestration, Berlioz skillfully balances moments of overwhelming intensity with passages of great intimacy and delicacy, such as the serene “Sanctus”, which features the solo tenor and a delicate interplay of chorus and orchestra.

Innovation and Legacy

Berlioz’s Requiem broke new ground in choral-orchestral writing. His use of space was especially innovative: by placing brass ensembles around the audience, he created an immersive and multidirectional sound that foreshadowed modern surround-sound techniques. He wrote that “if I were threatened with the destruction of all my works save one, I should crave mercy for this one.”

Although it was written for a specific political occasion, the work transcended its original purpose and gained a place in the concert repertoire as a powerful artistic statement about mortality, divine judgment, and human emotion.

The Grande Messe des Morts influenced many composers after Berlioz, including Verdi and Mahler, who admired the dramatic possibilities of large-scale religious music. Mahler’s own monumental symphonies, especially the Resurrection Symphony, reflect a similar grandeur and philosophical depth.

Reception and Performances

The initial reception of the work was generally positive, although its massive scale made performances logistically and financially challenging. Over time, however, it has come to be regarded as one of the great masterpieces of 19th-century sacred music.

Modern performances, while still relatively rare due to the required resources, are considered major musical events. Leading conductors such as Colin Davis, Charles Dutoit, and Sir Simon Rattle have championed the work, and it has been recorded several times to critical acclaim.

Conclusion

Hector Berlioz’s Grande Messe des Morts is more than a Requiem—it is a towering statement of Romantic expression, combining personal intensity with national grandeur. Through its unprecedented orchestration and emotional scope, it remains one of the most powerful works ever composed for chorus and orchestra, a testament to Berlioz’s genius and to the eternal human confrontation with death and remembrance.

Comments are closed