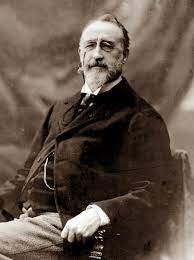

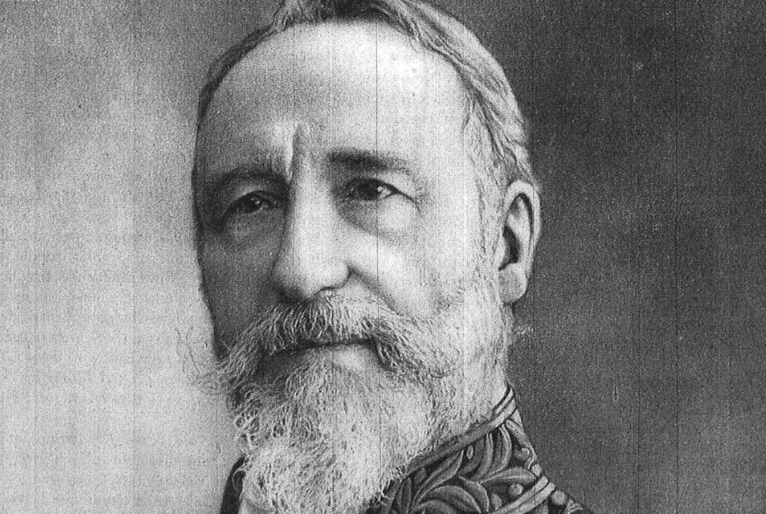

Theodore Dubois – A Complete Biography

Introduction

Théodore Dubois (24 August 1837 – 11 June 1924) was a French Romantic composer, organist, influential pedagogue, and eventually director of the Paris Conservatoire. Though he aspired to make his reputation on the operatic stage, Dubois became best known for sacred music, organ works, and widely used theory treatises. His career traced the arc of the French musical establishment from the Second Empire into the early twentieth century, culminating in a contentious final chapter around the 1905 Prix de Rome affair.

Childhood

Dubois was born in Rosnay, in the Marne near Reims, the son of Nicolas Dubois, a basket maker; his grandfather was a village schoolmaster. Early piano instruction came from Louis Fanart, choirmaster of Reims Cathedral, and local patrons helped the gifted boy access broader training. These formative experiences grounded his lifelong attachment to church music and practical musicianship.

Youth

Admitted to the Paris Conservatoire in 1854 under director Daniel Auber, Dubois studied piano with Antoine-François Marmontel, organ with François Benoist, harmony with François Bazin, and composition with Ambroise Thomas. He accumulated Premiers Prix in harmony, fugue, and organ, then captured the coveted Prix de Rome in 1861 with the cantata Atala. After his residency at the Villa Medici in Rome—where he befriended fellow laureate Jules Massenet—he returned to Paris in 1866.

Adulthood

Back in Paris, Dubois was appointed maître de chapelle at Sainte-Clotilde (working alongside César Franck) and soon became a founding member of the Société Nationale de Musique in 1871. He joined the Conservatoire faculty that year as professor of harmony, later teaching composition, and in 1877 succeeded Camille Saint-Saëns as organist of the church of La Madeleine. In 1896 he rose to director of the Paris Conservatoire, continuing a conservative academic line inherited from Ambroise Thomas.

Dubois’s tenure ended abruptly in June 1905 after a public scandal over the Conservatoire faculty’s handling of Maurice Ravel’s repeated attempts at the Prix de Rome. The controversy led to Dubois’s early retirement and Gabriel Fauré’s appointment to modernize the institution.

Even after retirement he remained active in Parisian musical circles. Privately, he was more open-minded than his official image suggested, admiring works like Wagner’s Parsifal and following newer harmonic languages, even as his public pedagogy remained traditional.

Major Compositions

Although Dubois wrote across many genres, his reputation rests strongly on sacred and organ music, plus a handful of orchestral and chamber scores. Highlights include:

- Sacred music: Les Sept Paroles du Christ (1867), arguably his most enduring work, alongside masses and motets such as the popular Panis angelicus and the large-scale Messe de la Délivrance.

- Organ works: The Douze pièces pour orgue (1889) include the widely played Toccata in G (No. 3); he later issued the Douze pièces nouvelles (1893). These sets remain staples for organists.

- Orchestral and concert pieces: Concerto-Capriccioso for piano and orchestra (1876), Piano Concerto No. 2 (1897), Violin Concerto (1896), and programmatic works such as Symphonie française (1908).

- Chamber music: Works such as the Piano Quartet in A minor (1907) and smaller ensemble pieces (e.g., Terzettino for flute, viola, harp) show his elegant craft and clarity.

- Stage works: Though he longed for an operatic breakthrough, successes were modest—e.g., the one-act Le pain bis (1879) and the ballet La Farandole (1883).

In addition to composition, Dubois’s theory treatises shaped generations of musicians: Traité de contrepoint et de fugue (1901) and Traité d’harmonie théorique et pratique (1921) remained in pedagogical use well into the twentieth century and are central to his legacy as an educator.

Death

After the death of his wife Jeanne Duvinage in 1923, Dubois’s health declined; he died in Paris on 11 June 1924, aged 86. Obituaries marked the passing of a pillar of the French musical establishment—an “official” composer whose influence as organist, teacher, and theorist extended beyond his own catalogue.

Conclusion

Théodore Dubois’s career embodies the strengths and limits of fin-de-siècle French musical classicism: impeccable technique, stylistic restraint, and a commitment to institutional standards. If his operas never entered the repertory, his sacred works and organ writing continue to speak in concert halls and churches, and his textbooks—clear, systematic, and pragmatic—left a durable mark on pedagogy. Modern recordings and scholarship have helped reposition him not merely as a gatekeeper of tradition but as a craftsman whose best pages reward renewed attention.

Comments are closed