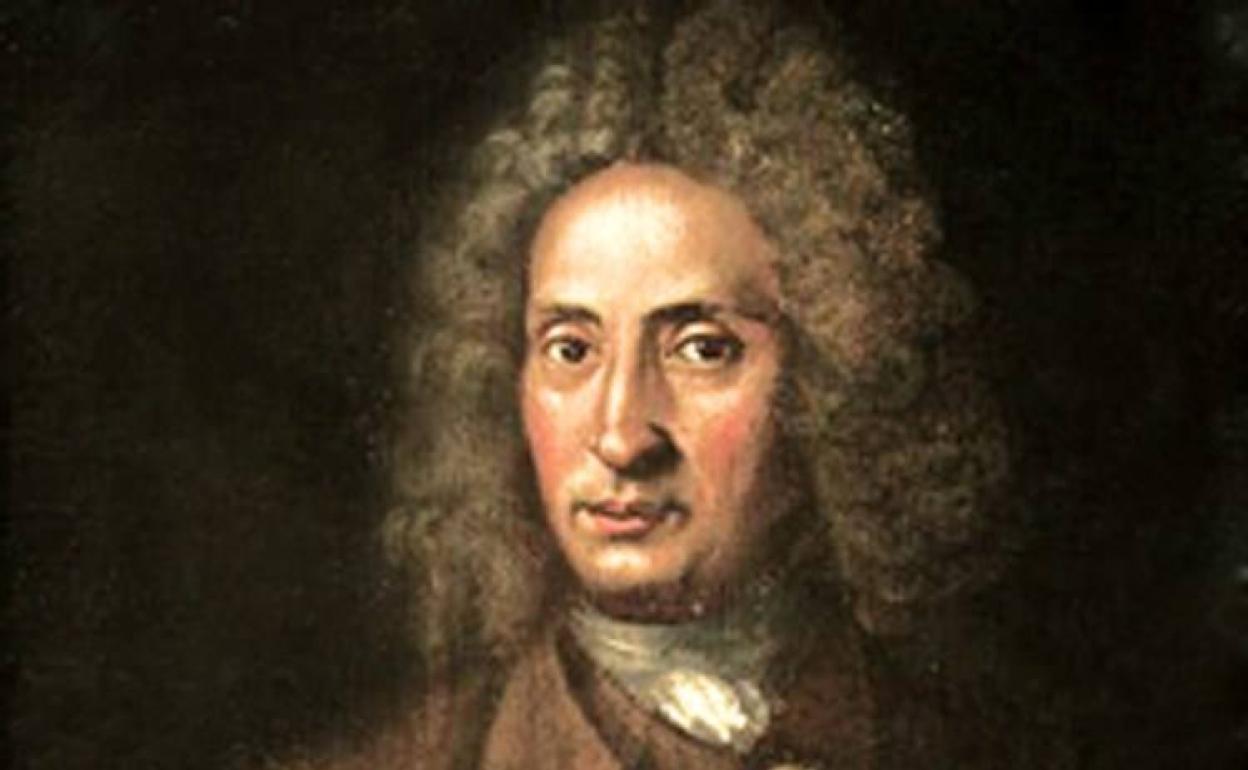

Tomaso Albinoni – A Complete Biography

Introduction

Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni (1671–1751) was a Venetian Baroque composer celebrated in his lifetime for operas and admired today above all for lyrical, finely crafted instrumental music—especially his concertos and chamber sonatas. A prosperous, independent “gentleman musician,” he never held a church or court post, which gave him unusual freedom for his era. Ironically, modern fame often circles around the Adagio in G minor, a piece now widely accepted to be a 20th-century creation by musicologist Remo Giazotto rather than an authentic work by Albinoni. The loss of many Albinoni manuscripts—particularly those once housed in Dresden—has further clouded the historical record, but surviving prints and archives still reveal a distinctive voice that influenced contemporaries and later masters alike.

Childhood

Albinoni was born in Venice on June 8 (or 14), 1671, the son of Antonio Albinoni, a wealthy paper merchant. Because the family was well-off, Tomaso could devote himself to music without seeking salaried employment. He studied violin and singing and often styled himself a dilettante di violino—not “amateur” in the modern sense, but a free artist outside institutional ties—an identity that helps explain the patchy documentation of his early career.

Youth

By his early twenties, Albinoni was composing and publishing with confidence. In 1694 his Op. 1 Sonate a tre appeared (dedicated to Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni), and that same year Venice heard his first opera, Zenobia, regina de’ Palmireni, at the Teatro SS. Giovanni e Paolo. Around 1700 he possibly served as a violinist to Charles IV, Duke of Mantua, and in 1701 issued the successful Op. 3 Balletti a tre, dedicated to Ferdinando de’ Medici. From the outset he worked as an independent composer rather than a salaried church or court musician, building his reputation through the opera house and printed instrumental collections.

Adulthood

In 1705 Albinoni married the singer Margherita Rimondi; the couple had several children. He continued to enjoy operatic success across Italy—in Venice, Genoa, Bologna, Naples, and elsewhere—while steadily publishing instrumental volumes. After the death of his father and financial reversals in 1721 (the same year his wife died), he accepted an invitation in 1722 to Munich from Elector Maximilian II Emanuel, directing performances there before returning to Venice. His last known opera, Artamene, appeared in 1740; documentation grows sparse thereafter, partly because wartime destruction later obliterated Dresden materials that had preserved aspects of his career.

Major Compositions

Albinoni published at least nine major collections of instrumental music between 1694 and the 1730s. Early highlights include Op. 1 Sonate a tre (1694) and Op. 2 Sinfonie e concerti a cinque (1700). Later sets—Op. 5 Concerti a cinque (1707), Op. 6 Trattenimenti armonici (c. 1711), Op. 7 and Op. 9 Concerti a cinque (1715 and 1722), Op. 8 Balletti & Sonate a tre (1722), and Op. 10 Concerti a cinque (1735/36)—cemented his reputation. Particularly important are the oboe concertos in Opp. 7 and 9: Albinoni was among the first Italian composers to feature the oboe as a solo instrument in published concerti, a practice that helped shape the instrument’s 18th-century concerto idiom. His printed works were widely reissued in Venice, Amsterdam, and London, and his themes drew the attention of J. S. Bach, who based several keyboard fugues on Albinoni materials.

Although he claimed a very large operatic output—dozens of titles produced in Venice and beyond—only a small fraction survives complete; much was never published, and some materials were later destroyed. Today, Zenobia (1694) and La Statira (1726) are among the few extant full scores, while many libretti attest to a once substantial stage presence.

A note on the famous “Adagio in G minor.” The piece commonly marketed as “Albinoni’s Adagio” is not his: it was crafted and copyrighted in the 1950s by Remo Giazotto, who said he built it on a figured-bass line and fragments he attributed to Albinoni from Dresden. Most reference works treat the Adagio as Giazotto’s composition, though later reports about fragmentary sources in his papers keep a sliver of debate alive. Either way, the Adagio’s popularity has overshadowed Albinoni’s authentic oeuvre, especially his oboe and string concertos.

Death

For many years scholars assumed Albinoni died around 1740 because a set of sonatas was issued “posthumously” in France. Parish records discovered later indicate he died in Venice on January 17, 1751—probably of diabetes mellitus. (Some older references still list 1750.) He was 79.

Conclusion

Tomaso Albinoni stands as a quintessential Venetian master whose graceful melodic invention and clear forms bridged stage and chamber, singer and instrumentalist. Freed from institutional constraints, he wrote on his own terms, leaving concertos and sonatas whose poise influenced contemporaries and later composers alike. Scholarship has helped rebuild his catalogue and context despite archival losses, encouraging modern listeners to hear beyond the misattributed Adagio and appreciate the authentic Albinoni: a “quiet master” of line, balance, and expressive restraint.

Comments are closed