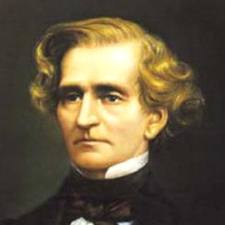

Hector Berlioz – A Complete Biography

Introduction

Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) stands as one of the boldest innovators of the Romantic era—an architect of modern orchestral color, a restless dramatist in sound, and a pioneering conductor whose tours spread his music across Europe. His scores fused literary imagination with unprecedented timbral daring, and his writings—especially the Treatise on Instrumentation—shaped how later composers and conductors thought about the orchestra. Today, works such as Symphonie fantastique, Roméo et Juliette, and the vast opera Les Troyens anchor his reputation as a composer of striking originality and dramatic power.

Childhood

Berlioz was born on December 11, 1803, in La Côte-Saint-André, in the French Alps, the elder son of Dr. Louis Berlioz and Marie-Antoinette Marmion. Educated largely at home by his father, he learned music informally: flute and guitar rather than the piano that trained most of his contemporaries. From an early age he composed small pieces for local ensembles and read voraciously—classical authors that would later echo throughout his music.

Youth

In 1821 his father sent him to Paris to study medicine, but the pull of the Opéra and the symphonic repertory (especially Gluck and Beethoven) proved irresistible. He entered the Paris Conservatoire to study composition with Jean-François Lesueur and began writing criticism. He fell under the spell of Shakespeare after English actors performed in Paris in 1827, and the Irish actress Harriet Smithson became the distant muse who would haunt his imagination and later marry him. Four determined attempts at the Prix de Rome culminated in victory in 1830, a turning point that confirmed his path as a professional composer.

Adulthood

Berlioz’s breakthrough came the same year with Symphonie fantastique (premiered December 5, 1830, Paris Conservatoire). In 1833 he married Harriet Smithson; though the marriage later foundered, those years saw a surge of creativity. He combined composing with journalism at the Journal des Débats and forged a second career as one of the century’s first star conductors, leading orchestras across Germany, Britain, and Russia. His Treatise on Instrumentation (1844) codified his insights into color and ensemble, while his later life mingled triumphs abroad with persistent resistance at home. In 1854 he married singer Marie (Maria) Recio; personal losses—her death in 1862 and that of his only son, Louis, in 1867—shadowed his final years.

Major Compositions

Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14 (1830). A five-movement “episode in the life of an artist,” it introduced the famous idée fixe and expanded the symphonic palette with shockingly vivid narrative imagery—from a glittering ball to a hallucinatory march to the scaffold and witches’ sabbath.

Harold en Italie, Op. 16 (1834). A viola-led symphony inspired by Byron; after its premiere, Paganini famously hailed Berlioz as Beethoven’s heir and endowed him with funds that enabled Roméo et Juliette.

Grande messe des morts (Requiem) (1837) and Te Deum (composed 1849; performed 1855). Monumental sacred scores that exploit spatial brass and choral forces, emblematic of Berlioz’s sense of sonic architecture.

Roméo et Juliette (1839). A “dramatic symphony” for soloists, chorus, and orchestra that translates Shakespearean drama into sweeping symphonic scenes.

La damnation de Faust (1846) and L’enfance du Christ (1854). Hybrid dramatic forms—a “dramatic legend” and a “sacred trilogy”—that reveal Berlioz’s flair for narrative pacing and choral writing.

Les Troyens (1856–58). Berlioz’s grand five-act opera on Virgil, his most ambitious project. Only the final three acts were staged during his lifetime (as Les Troyens à Carthage, 1863); the complete work would gain full recognition only in the 20th century.

Béatrice et Bénédict (1862). A witty late opera after Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, written for Baden-Baden.

His catalog also includes overtures such as Le Carnaval romain and Le Corsaire.

Death

Berlioz’s last major tour, to St. Petersburg and Moscow in 1867, exhausted him. He died in Paris on March 8, 1869, aged 65, and was buried in Montmartre Cemetery alongside his two wives. The late 19th and early 20th centuries gradually vindicated his stature, as fuller performances and recordings revealed the scope of his achievement.

Conclusion

Berlioz’s legacy rests on the fusion of literary imagination, dramatic instinct, and orchestral innovation. He expanded what an orchestra could express, anticipated modern conducting practice, and proved that symphonic design could bear the weight of psychological and theatrical narrative. Once polarizing, his music is now widely recognized as that of a “dramatic musician of the first rank,” and Les Troyens—alongside the Fantastique and choral-symphonic masterworks—confirms him as a singular, trailblazing voice of the 19th century.

Comments are closed