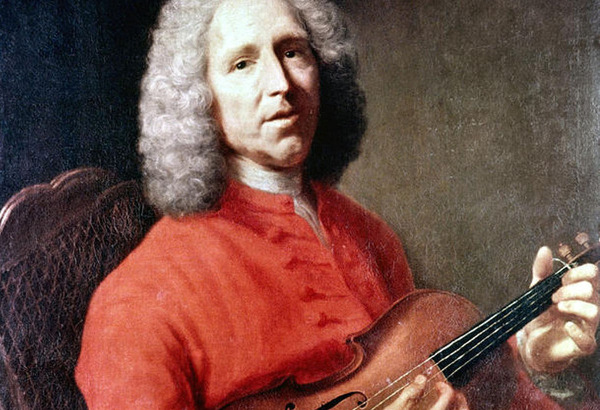

Jean Philippe Rameau – A Complete Biography

Introduction

Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764) stands as the towering French composer and music theorist of the later Baroque, the figure who revitalized French opera after Lully and codified a modern understanding of tonal harmony. His double legacy—stage masterpieces and groundbreaking theoretical treatises—made him a central reference point for 18th-century musical thought and practice.

Childhood

Rameau was born in Dijon and baptized on September 25, 1683. His father, an organist, oversaw his earliest training, a path that set the boy toward church posts and practical musicianship long before fame arrived. His provincial upbringing rooted him in a tradition of church music while cultivating his first skills at the keyboard.

Youth

As a young man, Rameau moved between posts and cities, taking up organist positions in several towns. He spent time in Milan and later Paris, where he published his first harpsichord collection in 1706. These years forged his identity as both a virtuoso keyboard composer and a working church musician. Even then, he was beginning to develop the theoretical ideas that would eventually change European music.

Adulthood

By the 1720s, Rameau settled in Paris, where his career took decisive shape. In 1722, he published the Traité de l’harmonie, a groundbreaking theoretical treatise that introduced the concept of chords having roots and harmony as music’s generative force. He continued this work with further writings such as the Nouveau système de musique théorique (1726) and Génération harmonique (1737), which refined his overtone-based theory of harmony. These works presented music through the lens of scientific reasoning, echoing Enlightenment ideals.

At the age of 50, Rameau achieved fame as an opera composer with the premiere of Hippolyte et Aricie in 1733 at the Académie Royale de Musique. Its daring harmonies and orchestral colors provoked fierce debate, pitting traditionalists loyal to Lully against supporters of Rameau’s modern style. This controversy followed his works for decades, but it also cemented his reputation as a daring innovator.

Major Compositions

Rameau’s output covers harpsichord music, chamber works, theoretical treatises, and especially operas that reshaped French lyric theater.

- Operas and opéra-ballets. His stage works include Hippolyte et Aricie (1733), Les Indes galantes (1735), Castor et Pollux (1737, revised 1754), Dardanus (1739, revised 1744 and 1760), Zoroastre (1749, revised 1756), La princesse de Navarre (1745, with Voltaire), Les Paladins (1760), and his final tragédie lyrique Les Boréades, left unstaged at his death. These operas expanded orchestral timbre, pushed harmonic boldness, and integrated dance into dramatic structure.

- Keyboard and chamber music. Rameau’s harpsichord collections (starting in 1706) feature expressive character pieces like La poule, Les tendres plaintes, and Les Sauvages. His Pièces de clavecin en concerts (1741) gave the harpsichord a new prominence in chamber ensembles.

- Theoretical writings. His treatises, especially the Traité de l’harmonie, defined modern tonal theory with concepts of chord roots, inversions, and the “fundamental bass,” influencing theorists and composers for generations.

By the 1740s and 1750s, Rameau had become the dominant figure of French opera, with a steady stream of new works and revisions regularly performed in Paris.

Death

Jean-Philippe Rameau died in Paris on September 12, 1764, reportedly from a fever. He was buried at the church of Saint-Eustache. His passing was marked with tributes, and his reputation as both composer and theorist was already firmly established by the time of his death.

Conclusion

Rameau’s historical importance is twofold. As a composer, he transformed French opera with daring harmonies, orchestral imagination, and dramatic vitality, leaving a repertoire that continues to be revived. As a theorist, he provided the first systematic account of tonal harmony—introducing ideas of root, inversion, and the fundamental bass—that shaped centuries of musical analysis. The convergence of practice and theory in his career—keyboard virtuoso, opera innovator, and “scientific” explainer of music—makes him one of the quintessential musicians of the Enlightenment.

Comments are closed