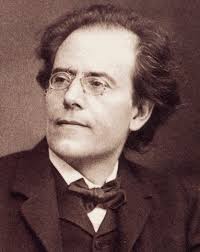

Gustav Mahler – A Complete Biography

Introduction

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) was an Austro-Bohemian composer and one of the most renowned conductors of his generation. His work forms a bridge between the 19th-century Austro-German tradition and the modernism of the early 20th century . While his conducting was widely acclaimed during his lifetime, his compositions only gained widespread popularity in the years following his death, after being suppressed in much of Europe during the Nazi era . Today, Mahler is considered one of the most important forerunners of 20th-century composition techniques and his works are among the most frequently performed and recorded in the classical repertoire.

Mahler’s life was marked by a sense of displacement and alienation. As he famously wrote, “I am three times homeless: a native of Bohemia in Austria; an Austrian among Germans; a Jew throughout the world” . This feeling of being an outsider, combined with a tumultuous childhood and a lifelong struggle with his health, profoundly influenced his music. His symphonies and songs are vast, emotionally charged works that explore the fundamental questions of human existence: life and death, love and loss, joy and despair.

Childhood

Gustav Mahler was born on July 7, 1860, in Kaliště (German: Kalischt), a village in Bohemia, then part of the Austrian Empire. He was the second of 14 children born to Bernhard Mahler, a Jewish distiller and tavern keeper, and Marie Herrmann. The family moved to the nearby town of Jihlava (German: Iglau) within months of Gustav’s birth, where he spent his childhood and youth.

Mahler’s early life was fraught with difficulties. His parents had a strained relationship, with his father, a self-educated man, often physically mistreating his mother. This created a deeply unsettling home environment for young Gustav, leading to a strong mother fixation and an alienation from his father. He also inherited his mother’s weak heart, a condition that would ultimately contribute to his early death at age 50. Furthermore, a constant backdrop of illness and death among his many siblings—only six of his 14 siblings survived infancy—deeply impacted him.

These early experiences are believed to have shaped Mahler’s tormented personality, contributing to the nervous tension, irony, skepticism, and obsession with death that pervaded his life and music. Despite these challenges, Mahler displayed prodigious energy, intellectual power, and an unwavering sense of purpose, traits likely inherited from his father’s side of the family .

His musical talent emerged at a very young age. Around four years old, he was captivated by the military music from a nearby barracks and the folk music sung by the Czech working people. He began reproducing these sounds on the accordion and piano, and soon started composing his own pieces. These early influences—military and popular styles, along with the sounds of nature—became significant sources of inspiration for his mature works.

At the age of 10, Mahler made his public debut as a pianist in Jihlava. By 15, his musical proficiency was such that he was accepted as a pupil at the prestigious Vienna Conservatory. He excelled in his piano studies, winning prizes in his first two years. In his final year (1877-1878), he focused on composition and harmony. Although many of his student compositions have not survived, his early work Das klagende Lied (The Song of Complaint), completed in 1880, already showcased distinctive features of his mature style, including ardent lyricism and a fascination with nature.

During his student days, Mahler formed a close friendship with fellow student and future song composer Hugo Wolf. He was also influenced by Anton Bruckner, whose Third Symphony made a profound impression on him. Despite his talent for composition, Mahler initially turned to conducting to secure a livelihood, reserving his composing for the summer vacations.

Youth

Mahler’s youth was largely defined by his burgeoning career as a conductor, a path he pursued out of necessity rather than initial primary ambition, as composing remained his true passion. The 17 years following his time at the Vienna Conservatory saw his rapid ascent in the conducting world. He began with humble engagements, conducting musical farces in Austria, and steadily climbed the ranks through various provincial opera houses. Notable appointments included those in Budapest and Hamburg, culminating in his prestigious appointment as artistic director of the Vienna Court Opera in 1897, at the age of 37 .

Despite his growing acclaim as a conductor, Mahler’s compositions during this early creative period were often met with public incomprehension, a challenge that would persist for much of his career. It is noteworthy that while his conducting life centered on the opera house, his mature compositional output was almost entirely symphonic. His songs, though numerous, were not traditional lieder but rather embryonic symphonic movements, some of which even formed the basis for his symphonies .

Mahler’s unique artistic aim, influenced by figures like Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt, was deeply autobiographical. He sought to express a personal worldview through music, believing that a symphony

should be a ‘world’ encompassing everything . For this purpose, song and symphony were more appropriate than the dramatic medium of opera: song for its inherent personal lyricism, and symphony for its subjective expressive power .

His first creative period as a composer yielded a symphonic trilogy, conceived on a programmatic basis. These early symphonies, though later stripped of their explicit programs, explored themes of pain, death, doubt, and the search for meaning in existence. Mahler drew inspiration from various sources, including Beethoven’s programmatic symphonies, Wagner’s music-dramas for their expanded scope and emotional expression, and Schubert’s chamber works for incorporating his own songs. He also famously integrated folk-inspired texts from Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Youth’s Magic Horn) into his works .

These early compositions, characterized by Mahler’s tense and rhetorical style, vivid orchestration, and ironic use of popular music, resulted in symphonies of wide contrasts, yet unified by his distinct creative personality and strong command of symphonic structure. His Symphony No. 1 in D Major (1888), for instance, is autobiographical of his youth, depicting the joy of life eventually overshadowed by an obsession with death, culminating in an arduous and brilliant finale .

Adulthood

Mahler’s adulthood was dominated by his dual roles as a celebrated conductor and a prolific, though often misunderstood, composer. His tenure as artistic director of the Vienna Court Opera from 1897 to 1907 marked the pinnacle of his conducting career. During this period, he was lauded for his innovative productions and his insistence on the highest performance standards, establishing his reputation as one of the greatest opera conductors, particularly for his interpretations of works by Wagner, Mozart, and Tchaikovsky.

However, his time in Vienna was also fraught with challenges. Despite his conversion to Catholicism to secure the prestigious post, Mahler faced persistent opposition and hostility from the anti-Semitic press . This constant pressure, combined with his demanding conducting schedule, meant that composing remained largely a part-time activity, confined mostly to his summer holidays.

Mahler’s personal life during his adulthood was equally complex. In 1902, he married Alma Schindler, a talented and beautiful woman 19 years his junior. Their relationship was intense and often turbulent. The couple had two daughters, Maria Anna and Anna Justine. A devastating blow came in 1907 with the death of their elder daughter, Maria Anna, at the tender age of five. This tragedy, coupled with Mahler’s diagnosis of a serious heart condition (a mitral valve defect) in the same year, profoundly impacted him and strained his marriage.

Seeking a new environment and perhaps an escape from the pressures in Vienna, Mahler moved to New York in 1908. He took on conducting roles at the Metropolitan Opera and later became the conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in 1909. His arrival in New York brought him renewed acclaim, and he embraced this new chapter with characteristic intensity, striving for the highest musical standards .

Despite his professional successes, Mahler’s health continued to decline. The bacterial infection he contracted, combined with his pre-existing heart condition and the lack of effective antibiotics at the time, left him with no hope of recovery. In early 1911, he expressed a wish to die in Vienna, the city with which he had such a profound love-hate relationship. He made the arduous journey back to Vienna, where he passed away shortly after .

Mahler’s later compositions reflect a shift towards greater introspection and a search for peace rather than grand climaxes. Works like Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth) and his Ninth Symphony, written after the pivotal year of 1907, showcase a more delicate and sparing texture, often culminating in a sense of resignation and fading into silence . His music continued to push the boundaries of harmony, rhythm, and sound color, making him a significant forerunner of 20th-century musical modernism.

Major Compositions

Gustav Mahler’s compositional output, though relatively limited due to his demanding conducting career, is monumental in scope and emotional depth. His works are primarily symphonies and song cycles, often conceived on an immense scale and embracing profound philosophical subjects such as love, hate, joy, terror, nature, innocence, and death . He expanded the traditional symphonic form, often incorporating vocal soloists and choruses, and stretching the boundaries of tonality.

Mahler’s symphonies are often grouped into three creative periods, each producing a trilogy. His first period includes:

•Symphony No. 1 in D Major (1888): Nicknamed the “Titan,” this symphony is autobiographical, depicting the journey from youthful exuberance to a confrontation with death. It famously incorporates a macabre funeral march based on a children’s song .

•Symphony No. 2 in C Minor (1894): Known as the “Resurrection” Symphony, it is a vast choral symphony exploring themes of death, judgment, and redemption. It features vocal soloists and a chorus, setting texts from Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock’s ode “Die Auferstehung” (The Resurrection) and Mahler’s own verses .

•Symphony No. 3 in D Minor (1896): Mahler’s longest symphony, it is a programmatic work that depicts the hierarchy of creation, from inanimate nature to divine love. It includes movements with mezzo-soprano, women’s chorus, and boys’ chorus .

The middle period of his symphonic output includes:

•Symphony No. 4 in G Major (1900): A more intimate work compared to its predecessors, it concludes with a soprano solo setting a text from Des Knaben Wunderhorn depicting a child’s vision of heaven .

•Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp Minor (1902): This purely instrumental symphony marks a shift in Mahler’s style, moving away from explicit programmatic elements. It is famous for its Adagietto, a tender movement often performed separately .

•Symphony No. 6 in A Minor (1904): Known as the “Tragic” Symphony, it is a powerful and pessimistic work, notable for its use of a hammer blow in the final movement, symbolizing fate .

His final creative period produced:

•Symphony No. 7 in E Minor (1905): Often called “Song of the Night,” this symphony is characterized by its nocturnal atmosphere and unique instrumentation .

•Symphony No. 8 in E-flat Major (1907): Nicknamed the “Symphony of a Thousand” due to the massive orchestral and choral forces it requires, it is a setting of the Latin hymn “Veni Creator Spiritus” and the final scene of Goethe’s Faust . Its premiere was one of the greatest triumphs of Mahler’s career .

•Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth) (1908): A song-symphony for two vocal soloists and orchestra, setting ancient Chinese poems. It reflects Mahler’s growing introspection and resignation .

•Symphony No. 9 in D Major (1909): Mahler’s last completed symphony, it is a profound and contemplative work that seems to ebb away into silence, often interpreted as a farewell to life .

•Symphony No. 10 (unfinished, 1910): Only the first movement (Adagio) was completed and fully orchestrated by Mahler. Various performing versions of the entire symphony have been created by others, offering a glimpse into his evolving style .

Beyond his symphonies, Mahler’s song cycles are equally significant. These include Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer), Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Deaths of Children), and settings from Des Knaben Wunderhorn. These songs often served as melodic and thematic sources for his symphonies, blurring the lines between the two forms . Mahler’s innovative use of popular musical elements, vivid orchestration, and emotional intensity ensured his lasting influence on 20th-century composers.

Death

Gustav Mahler’s final years were marked by a series of personal tragedies and a rapid decline in health. In 1907, he received a devastating diagnosis of a congenital heart defect, a condition he had inherited from his mother. This news came shortly after the tragic death of his elder daughter, Maria Anna, from scarlet fever and diphtheria at the age of five. These events deeply affected Mahler, exacerbating his already melancholic disposition and placing immense strain on his marriage to Alma.

Despite his deteriorating health, Mahler continued to pursue his musical career with characteristic vigor. He left Vienna in 1908 for New York, where he took on the demanding roles of conductor at the Metropolitan Opera and later the New York Philharmonic. His performances in America were met with great acclaim, and he found a new sense of purpose and energy in this new environment.

However, his health continued to worsen. In February 1911, Mahler contracted a serious bacterial infection, likely endocarditis, which, given the lack of antibiotics at the time, offered no hope of recovery. Recognizing the gravity of his condition, Mahler expressed a strong desire to return to Vienna, the city that had been both a source of immense professional triumph and personal anguish .

He embarked on the arduous transatlantic journey back to Europe, arriving in Vienna in a severely weakened state. Gustav Mahler died on May 18, 1911, just six weeks before his 51st birthday. According to his wife Alma, his last words were “Mozart – Mozart!” . He was buried in the Grinzing Cemetery in Vienna, as he had requested, next to his daughter Maria Anna.

Mahler’s death came before he could witness the full impact of his later works. He never heard a complete performance of Das Lied von der Erde or his Ninth Symphony. His passing marked the end of an era, but his music, though initially met with mixed reactions, would eventually gain the recognition and admiration it deserved, solidifying his place as one of the most significant composers in Western classical music.

Conclusion

Gustav Mahler’s life was a testament to artistic perseverance in the face of profound personal and professional challenges. Born into a turbulent family environment and grappling with a lifelong sense of being an outsider, Mahler channeled his complex inner world into a body of work that redefined the symphony and song cycle. His music, characterized by its vast emotional range, innovative orchestration, and philosophical depth, initially bewildered many of his contemporaries. Yet, Mahler, a visionary conductor who demanded perfection, remained steadfast in his compositional pursuits, often dedicating his precious summer months to creating the works that would secure his legacy.

His symphonies, often described as “worlds” in themselves, explored the full spectrum of human experience, from the innocent joy of folk melodies to the profound despair of loss and the existential quest for meaning. Mahler’s willingness to incorporate disparate elements—from military fanfares and folk tunes to sublime spiritual contemplation—into his grand musical structures was revolutionary. This eclectic approach, combined with his expansion of orchestral forces and his daring harmonic language, positioned him as a crucial transitional figure between the Romantic era and the dawn of modernism.

Comments are closed